Hungarian Goose Down

A Timeless Heritage of Warmth & Craftsmanship

Goose Farming Became a Family Business

In early 19th-century Hungary, geese were more than barnyard animals—they were a pillar of household survival. Families across the Alföld plains and Transdanubian hills raised flocks for meat, liver, fat, feathers, and especially down. It was a system of complete use: nothing wasted, every part with value.

Children scattered grain in the yard, mothers plucked feathers and sorted down, and grandparents remembered which lines of geese produced the softest clusters. Geese required little investment but much labor: plucking was done by hand, down dried in the sun, then stored in cotton sacks. Some families stitched pillows and comforters for their own dowries and winter beds, while others sold raw feathers at local fairs.

What began as subsistence soon became trade. Goose farming provided backup income when crops failed and gave women a tangible role in the family economy. By mid-century, it was clear: geese were not just animals of the yard, but quiet engines of rural life.

Childhood moments in Hungarian villages

Hungary's White Gold

By the mid-19th century, goose down had earned a reputation beyond the household. Women gathered in the evenings to sort, fluff, and clean it, transforming a byproduct into something of real value. The purest clusters were guarded like treasure, saved for sale or reserved for daughters’ dowries.

A fine pillow or comforter could command a strong price at market. In regions where cash was scarce, down became its own form of wealth—sometimes handed down across generations, much like land or jewelry. For rural women, this labor meant more than household duty; it offered pride, stability, and a modest independence.

Down was weightless, yet it carried the weight of security. In these quiet, domestic rituals, Hungary’s “white gold” was already on its way to becoming known far beyond village borders.

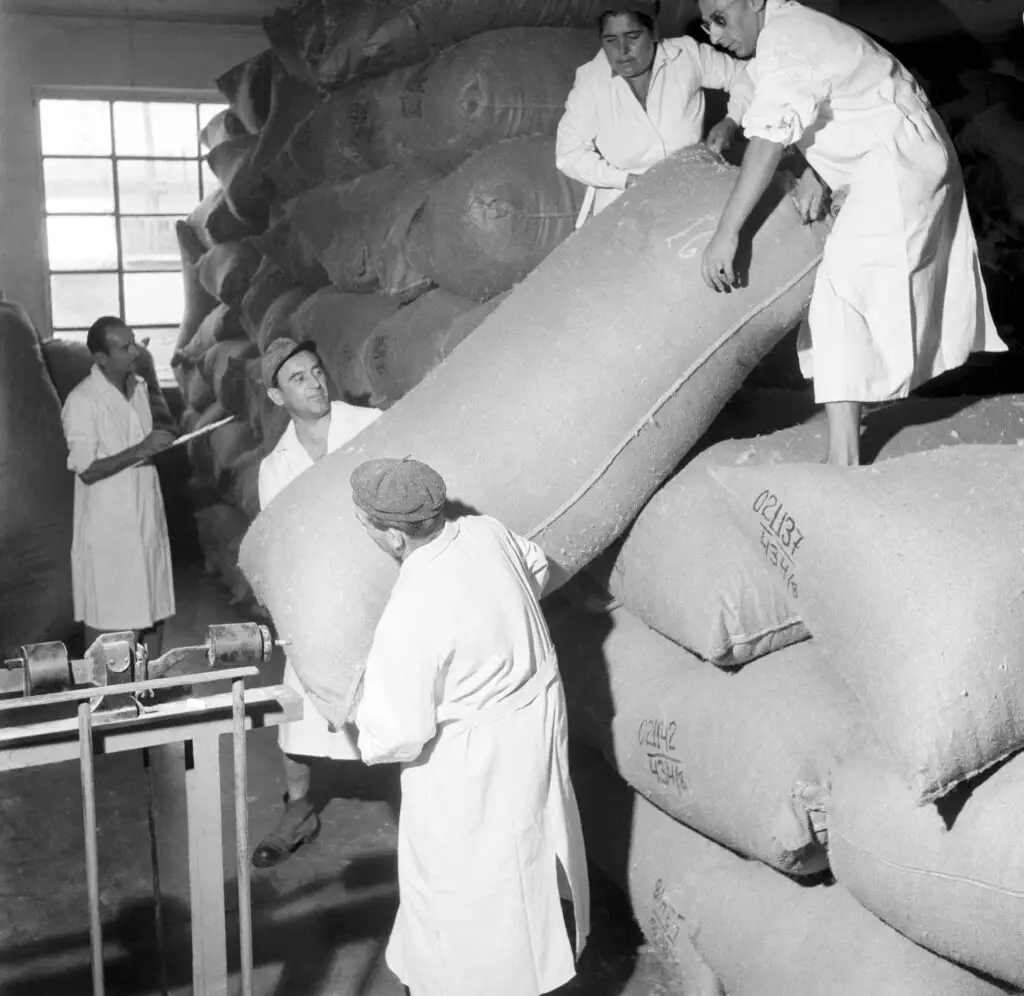

The art of down sorting

Softness Sought Across the Empire

As railways expanded, Hungarian down moved from kitchens to marketplaces across the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Merchants who once traveled by cart now arrived by train, purchasing sacks of down at rural fairs and carrying them to Vienna, Prague, and beyond.

Feather traders became familiar figures in village life, bargaining with families who had spent the long winters plucking and sorting by firelight. The exchange linked two worlds: the slow, steady rhythm of rural households, and the bustling, cosmopolitan markets of the empire.

Hungarian down stood apart—soft, resilient, long-lasting. Its reputation spread among upholsterers, bedding makers, and even fashion houses. This was the moment when a household staple became a sought-after commodity, laying the groundwork for Hungary’s enduring status as Europe’s source of softness.

A bustling day at the market

Inside the Chambers of the Aristocracy

By the late 19th century, goose down had reached the highest echelons of society. In aristocratic homes and grand hotels alike, bedding was no longer simply practical—it was a declaration of refinement.

Ornate headboards rose above beds dressed in crisp linen and heavy curtains. At the center lay the comforter, hand-filled with Hungarian goose down. To noble families, these were not just objects of rest, but emblems of wealth and permanence. Guests read the bedchamber as carefully as the drawing hall, where a well-stuffed pillow spoke as eloquently of privilege as a chandelier.

Yet even in these gilded settings, intimacy remained. A down-filled pillow carried the warmth of nightly rest, the weight of dowry traditions, and secrets whispered across generations. From rural yards to palace chambers, goose down bridged worlds—its softness both survival and symbol.

Royal chamber in Esterházy Castle

Down Enters Grand Hotels

As the 19th century drew to a close, travel in Hungary was transforming. Railways and steamships made journeys easier, and a new class of travelers sought more than shelter—they sought refinement. Grand hotels rose from Budapest’s boulevards to the shores of Balaton, competing not only with architecture and service but with something more personal: the promise of a good night’s sleep.

Goose down pillows and comforters quickly became part of this competition. What had once been a household treasure was now a mark of sophistication in suites. To rest on Hungarian down was to experience a softness that set these hotels apart from simpler inns. Guests noticed, and the quality of sleep became part of how they judged the quality of a stay.

Hotel managers soon recognized that bedding mattered as much as chandeliers or fine dining. They sourced Hungarian goose down from trusted merchants, ensuring their suites offered not just clean sheets but genuine comfort.

In 1898, goose down was no longer only the domain of dowries and family bedrooms. It had stepped into the public sphere—becoming a symbol of status, comfort, and modern hospitality from Budapest to Balaton.

Grand Hotel Hungaria, Budapest

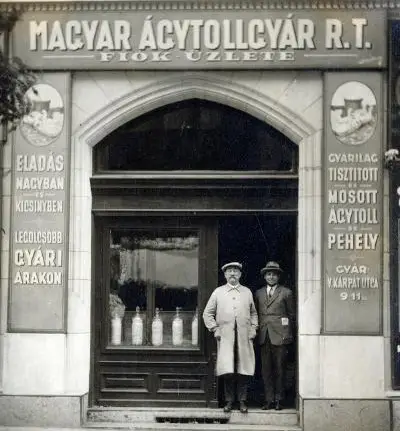

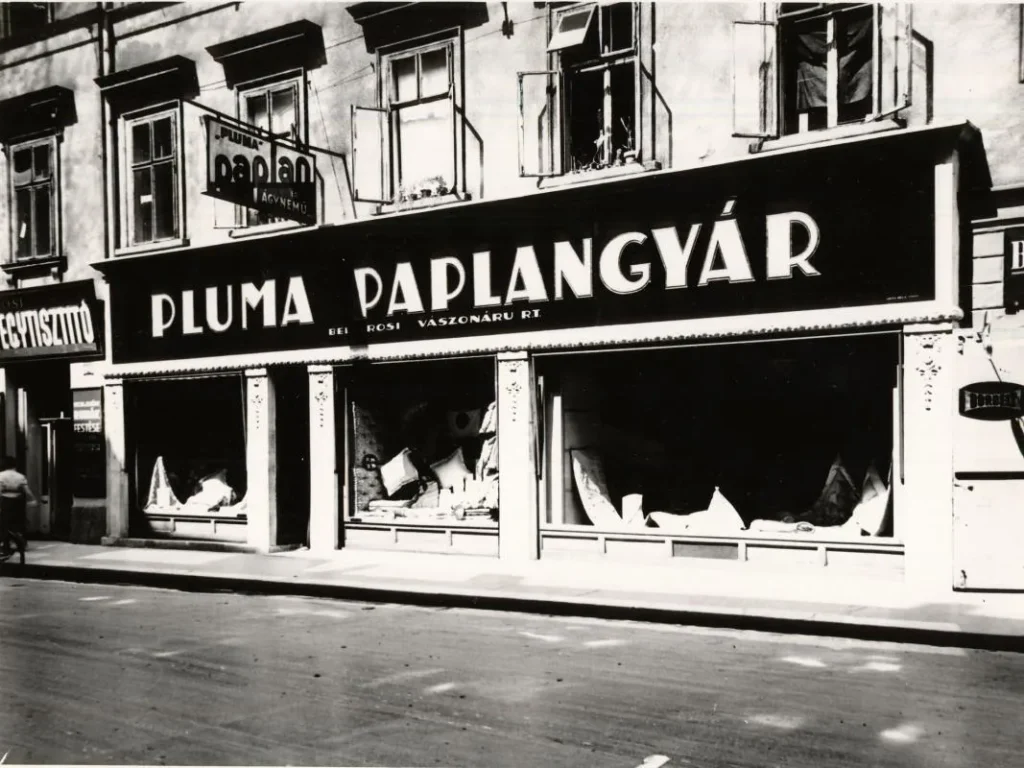

Down Goes Downtown

By the early 1920s, Hungary was undergoing a quiet transformation. After the First World War and the Treaty of Trianon, the country was smaller, more fragile—but innovation found a way forward. In cities like Budapest, Győr, and Debrecen, something new appeared between the bakeries and the tailor shops: down and feather stores.

Until then, goose down was a village affair—cleaned and sorted by hand, passed down through generations, and sold discreetly at rural fairs or to traveling traders. But in 1922, the first urban shops dedicated solely to down and feather products began to open their doors.

Behind polished glass and painted signage, bundles of down were no longer hidden. They were measured, labeled, and priced. Pillows and comforters were stacked neatly on shelves, not folded in aprons or wrapped in cloth. Salesmen wore suits, not smocks. For the first time, softness was branded.

This shift marked more than a change in setting. It was the beginning of down’s professionalization—a step toward quality standards, factory production, and broader recognition. Urban consumers, increasingly interested in home comfort, embraced the idea that true softness could now be bought, not just inherited.

The down trade was no longer whispered about in kitchens—it spoke clearly through storefronts and invoices.

Early bedding stores in Hungary

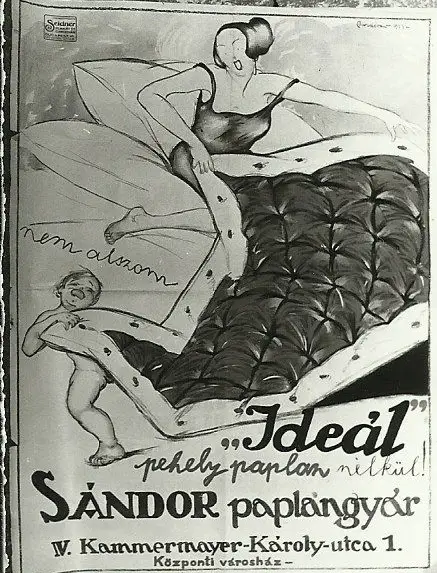

From Necessity to Desire

In the depths of the Great Depression, goose down in Hungarian villages was more than comfort—it was currency. At rural markets, sacks of down quietly changed hands for shoes, flour, or firewood. When money was scarce, softness itself became a form of survival. A single pillow’s worth of filling could mean a warm meal, and a comforter’s worth could keep a family supplied through winter.

Yet the 1930s were not only a decade of scarcity. As the years progressed, another story of down unfolded in the cities. Urban department stores and manufacturers discovered that down could be sold not just as bedding, but as aspiration. Bold advertisements appeared in newspapers and posters, often humorous, sometimes glamorous, suggesting that a proper night’s sleep was no longer merely a necessity—it was a mark of refinement and success.

The contrast was striking. What had been bartered out of need in village markets became marketed as desire in Budapest and beyond. Families in the countryside still guarded every feather for survival, while city dwellers were encouraged to dream of duvets as symbols of modern living.

Hungarian down, once a quiet part of household survival, had entered a double life. It was at once a means of endurance in hard times, and a rising emblem of elegance in a decade caught between struggle and style.

Bedding advertisement in the 1900s

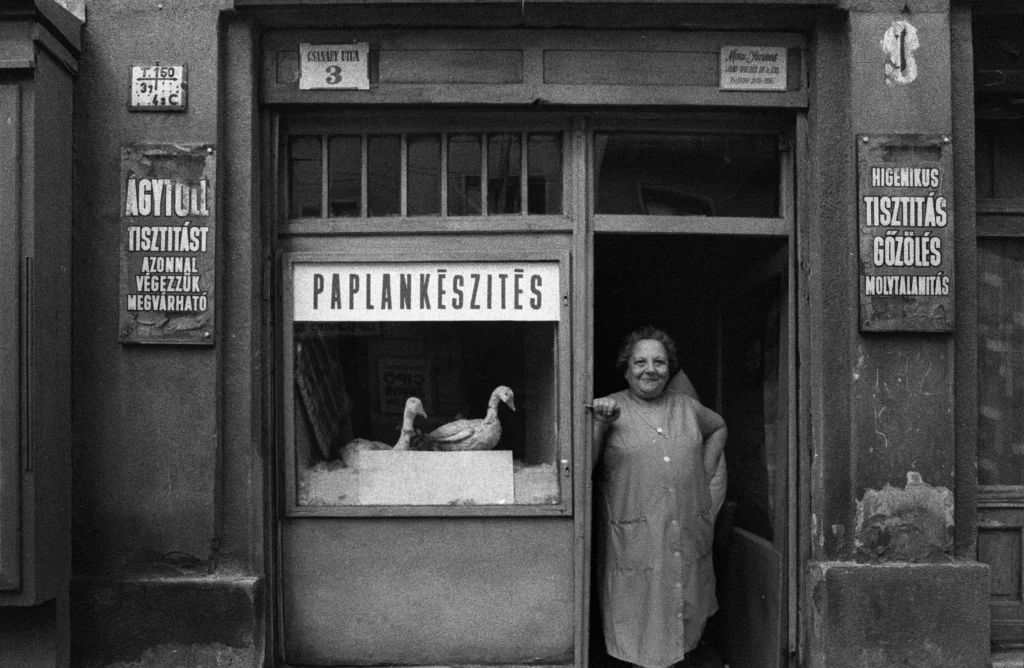

Hidden Hands Behind Pillows

In workshops tucked between apartment buildings and behind courtyard doors, a quiet craft carried on. Even as official systems shifted and industries became centralized, these small, often family-run spaces quietly endured—keeping tradition alive through steady hands and well-worn tools.

Inside, everything was done by hand. The down was steamed, fluffed, and gently filled into ticking fabric. Old duvets were taken apart, refreshed, and sewn back together with practiced skill. The tools were simple, but the knowledge behind them ran deep—passed from mothers to daughters, neighbor to neighbor.

These weren’t factories. There were no loud machines, no standardized lines. Just warm steam, shared know-how, and an understanding of softness that no textbook could teach. Every comforter held traces of personal history—sometimes even down saved from a grandmother’s pillow, brought in to be reborn.

Customers didn’t need advertisements. They came because they trusted the hands behind the stitching. They knew these women worked not just with fabric, but with intention.

In an era of rules and reforms, these quiet workshops offered something different: constancy, care, and the enduring comfort of something truly made by hand.

A duvet shop on the corner

Smuggled Softness

Behind the Iron Curtain, softness moved in silence—drifting westward despite the barriers of the 1970s. Though officially restricted, Hungarian goose down became a quiet currency among diplomats, émigrés, and curious travelers. Not in bulk, not in crates—but tucked between folded clothes, stitched into linings, or passed along in hushed exchanges.

To the West, Hungarian down was exotic and coveted—an open secret among those who’d felt it. It didn’t have brand names or labels, but it had a reputation: light as air, rich in comfort, and impossible to fake.

A pillow was often packed as personal bedding. A comforter, tightly rolled, was declared as laundry. Some stories tell of coats lined with down so thick they needed no overcoat—except to mask what was inside. Others speak of embassy kitchens, where the real goods weren’t just paprika or Tokaji wine, but a pillow slipped under a guest’s arm before they returned to Vienna, London, or beyond.

This wasn’t just smuggling. It was cultural leakage—the movement of something warm, handmade, and deeply human across a dividing line that tried to separate lives.

Hungarian down didn’t wait for permission. It crossed borders long before export papers were drawn up. And in guest rooms across the West, quiet luxury arrived—not through catalogs, but through memory, rumor, and the kindness of those who still believed softness should be shared.

Suitcases under scrutiny

Hungary Became the World’s No. 2 Down Exporter

Quietly but decisively, Hungary rose to the top ranks of the global down trade—becoming one of the world’s foremost suppliers of goose down. While China held the top spot by scale, Hungary stood out for something else entirely: quality.

Behind this rise was a vast, state-coordinated system. Farms specialized in goose breeding, down was processed in industrial plants, and export channels were streamlined through government agencies. It was a tightly organized pipeline—one that moved feathers from rural fields to factories, and eventually into crates bound for Europe, Japan, and beyond.

Hungarian down earned a name for itself not just through quantity, but consistency. Buyers knew what they were getting: large clusters, exceptional loft, and down that held its shape and softness over time. In trade fairs and catalogues, Hungarian origin became a mark of excellence.

And yet, there was something almost poetic in it—a small Central European country, landlocked and modest in size, quietly exporting comfort across continents. Not through noise or mass marketing, but through a product so light it traveled almost unnoticed—until it reached the bedroom.

Hungarian Down Beyond the Curtain

For decades, Hungarian goose down had existed behind barriers—political, economic, and geographic. It moved quietly across borders, carried in private hands rather than promoted or branded. But in 1989, with the fall of the Iron Curtain, everything changed. What had been hidden was ready to be seen.

Producers of Hungarian goose down, once restricted to domestic sales or tightly controlled state exports, could now connect directly with international buyers. Family-run workshops resurfaced, and private businesses began to re-emerge. The shift wasn’t immediate, but momentum was building—powered by generations of experience in producing world-class down.

When it entered the global luxury bedding market, Hungarian goose down wasn’t an unknown product. It was a long-coveted material finally available in the open. Designers, premium bedding brands, and quality-focused hotels who had only heard of its reputation could now experience it for themselves: the lightness, the resilience, and the unmistakable warmth shaped by decades of meticulous craftsmanship.

As borders opened, so did possibilities. And for the first time in generations, Hungarian goose down could travel freely—not just between countries, but into the international spotlight it had long deserved.

The Fall of the Iron Curtain

Hungarian Down Finds a Passport

By the mid-1990s, Hungarian goose down had fully stepped onto the international stage. It now appeared in catalogues, and behind boutique glass—its name printed proudly on luxury bedding product tags.

High-end brands around the world took notice. They weren’t just looking for softness—they were seeking origin stories, materials with depth, and craftsmanship with a clear heritage. Hungarian goose down offered all three. It was prized for its rare balance: incredibly warm yet featherlight, long-lasting yet naturally breathable.

Designers in Tokyo sourced it for modern futons. Prestigious hotel chains in New York requested it for their premium suites. European bedding houses, long familiar with Hungarian goose down’s reputation, began marketing it globally—celebrating not only the impressive fill power, but also the generations of expertise behind it.

For producers back home, this shift was more than economic—it was cultural. What had once been a quiet rural craft had become an internationally recognized symbol of excellence, trusted far beyond the fields where it began.

Hungarian goose down, after generations of staying close to home, had earned its passport—and a place among the world’s finest bedding materials.

The Plaza Hotel, New York

Hotel Ritz Paris, France

Park Hyatt, Tokyo

Craftsmanship in a High-Tech World

The 2010s were an age of speed. Clothing could be delivered overnight, electronics updated every year, and furniture assembled in minutes. Factories produced more than ever—fast, cheap, and uniform. Yet in the middle of this convenience, a countercurrent began to grow. People started looking for products that lasted—items made with intention, skill, and care rather than automation.

Hungarian goose down bedding found itself at the heart of this shift. For generations, it had been crafted by hand—down sorted for quality, shells sewn with precision, and every stitch checked for durability. In the 2010s, this way of working was no longer just tradition; it became a mark of prestige in the luxury bedding market.

Against a backdrop of mass-produced goods flooding global markets—often from large manufacturing hubs like China—Hungarian workshops offered something fundamentally different. They didn’t compete on price; they competed on truth, craftsmanship, and the tactile difference you can feel when something has been made by human hands. Customers investing in quality saw the contrast immediately: the resilience of a duvet sewn in a small Hungarian workshop far outlasted its mass-market counterpart.

Boutique bedding makers in Hungary leaned into this strength. They told the story of heritage and handcraft, of geese raised in the open air, and of down cleaned and sorted with care rather than harsh chemicals. Their marketing didn’t shout—it invited customers to slow down, to understand the value of choosing something they could keep for decades rather than replace in a few years.

Even in a world of online shopping and global shipping, Hungarian goose down bedding stood apart. It wasn’t chasing trends—it was standing against them. And in doing so, it became a quiet yet powerful symbol of authenticity, durability, and craftsmanship in a high-tech, throwaway world.

The art of handmade bedding

The Hidden Ingredient of European Hotel Comfort

By the late 2010s, the luxury hospitality industry had entered a new era. Guests no longer came to five-star hotels only for service and scenery—they came for rest, recovery, and the promise of leaving better than they arrived. Wellness suites, sleep programs, and curated bedding menus became part of the experience. Behind these offerings, Hungarian goose down bedding quietly remained a constant.

In alpine lodges, lakeside resorts, and grand city hotels across Europe, duvets and pillows filled with Hungarian goose down set the standard for premium hotel comfort. It wasn’t widely advertised, yet its qualities aligned perfectly with late-2010s trends: breathable in summer, insulating in winter, naturally hypoallergenic, and fully biodegradable. Hotels focused on sustainable luxury and authentic guest experiences found that Hungarian goose down told this story without a single marketing word.

Procurement managers, interior designers, and general managers knew the difference. Lower-cost fills—whether synthetic or mass-produced down from elsewhere—simply could not match the durability, loft, and year-round comfort of Hungarian goose down. In an era when guests expected the best sleep of their lives, these qualities became essential.

For travelers, the experience was seamless. They simply sank into crisp linen and weightless warmth, unaware that the bedding beneath them carried a heritage refined over generations. And as “quiet luxury” emerged as a global design movement, Hungarian goose down embodied it perfectly—subtle, enduring, and felt rather than seen.

Hotel St. Moritz, Switzerland

Hotel Kulm, Switzerland

Hotel Rosa Alpina, Italy

The Renaissance of Natural Materials

The conversation around comfort and home wellness has shifted. People no longer want just softness—they want softness with a story, and materials they can trust. In a world focused on sustainable living, natural materials such as Hungarian goose down or organic cotton have gained renewed attention. Consumers increasingly choose bedding and home goods that are renewable, biodegradable, and free from unnecessary chemicals.

Unlike polyester or mass-produced down from other regions, Hungarian goose down comforters and pillows offer qualities modern buyers value most: natural breathability, exceptional warmth-to-weight ratio, long-lasting loft, and full biodegradability. These same values are driving a wider return to authentic materials—products chosen not only for beauty and comfort, but for their environmental integrity.

Interior designers, wellness retreats, and luxury hotels are embracing spaces filled with natural textures and fibers. Hungarian down bedding, with its centuries-old heritage, fits seamlessly into this movement—providing a clean, breathable, chemical-free option that works year-round. Customers choosing Hungarian goose down today are making a conscious decision for quality, sustainability, and alignment with a global shift toward natural living.

The softness of natural materials